Durango Bill's

Paleogeography (Historical Geology) Research

Appendix to the Evolution of the Colorado River and its Tributaries (Part 7)

Colorado's Gore Range

by

Bill Butler

This mountain range

(and the area northeast of it) is significant as it reveals

the early history of the headwaters of the Colorado River. The

range has several curiosities including two major canyons that

cut through it. Tenmile Creek cut Tenmile Canyon and the

Colorado River cut Gore Canyon. A major question has been –

How did these streams get across the Gore Range to form the

canyons? It has been assumed that the range was uplifted

during the Laramide. However, this makes it very difficult to

form these breaches. The problem becomes much easier if we can

show the present Gore Range did not rise until Miocene time.

(Recent research implies much of this uplift has occurred in

the last 5 million years.) This allows lots of time for both

of these streams to be in place before the range rose.

First, let’s look at some of the unusual/unexpected phenomena that exist in the range.

1) Tenmile Creek cuts a SSW to NNE canyon through the range at about the 9,100 to 9,600 foot level. (Highway I-70 uses this canyon to get through the range.) Peaks exceed 12,000 feet within two miles on both sides of Tenmile Canyon.

2) The Colorado River has cut westward through the range at Gore Canyon. The floor of the canyon is at about 7,200 feet while the rim on both sides exceeds 9,300 feet within a mile of the river.

3) A dry abandoned valley (similar to Unaweep Canyon) cuts across the range a couple of miles south of Gore Canyon. At some time in the past a tributary to the Colorado River flowed east to west across the crest of the range through this abandoned valley.

4) Another high dry valley cuts across the range some 6 miles northwest of Gore Canyon at Gore Pass. At some time in the past, another tributary crossed the range from northeast to southwest through this abandoned valley. (The formation of this valley was probably helped by a NE-SW fault.)

5) Both Gore Creek and Service Creek start down the east side of the range and then double back through the crest to flow down the west side. In both cases, these streams use segments of ancestral rivers that crossed the crest of the range from east to west.

6) The heart of the Gore Range just north of Tenmile Canyon has a jagged, “young-looking” appearance as compared to the rounded Laramide age Front Range just 15 miles further east.

If we look at the area bounded by the Gore/Park Range to the west and the Medicine Bow and Front Ranges to the east, we find a broad area covered by early Tertiary deposits. The east to west Rabbit Ears Range splits this into North and Middle Parks although the Tertiary deposits wrap over the top of the range. Also there are splatterings of mid/late Tertiary volcanics across the top and to south of the Rabbit Ears Range. The Gore/Park Range itself has no Tertiary deposits except for a couple of Tertiary intrusions and some Tertiary lava flows near the west end of the Rabbit Ears Range.

The main feature of the Gore Range is Gore Canyon. Here, the Colorado River cuts a short, deep (over 2,000 feet), young-looking gorge across the crest of the range. If you smoothed out the contours across the gorge, the crest would be about 9,400 feet above sea level. Muddy Creek is a tributary that feeds into the Colorado before it cuts through Gore Canyon. At the north end of Muddy Creek’s drainage (off the top of the view) there are multiple potential exit routes that are less than 9,000 feet including Muddy Pass at slightly over 8,700 feet. To the east of Muddy Pass we have early Tertiary sediments and mid/late Tertiary lava flows overlying Cretaceous layers and still stay well under 9,400 feet. The Tertiary deposits indicate this area has never been over 9,400 feet.

There are two possible ways the Colorado River could have established a path across the Gore Range. Either (1) at some time in the past there was a higher sedimentary or pediment surface east of the range, or (2) the Colorado River established its westward course before there was a (significant) uplift of the range. It has always been assumed that case number (1) was true. However, given that alternate exit routes that stay under 9,400 feet have always been available, the evidence seems to support alternative (2). Thus, we offer the following model.

During the initial

Laramide uplifts, the Front Range was lifted to high

elevations and the current Gore/Park Range was only lifted

slightly. (Just enough so that the top sedimentary layers

would erode.) In between the two ranges, the headwaters of the

ancestral Colorado flowed north into Wyoming. Tenmile Creek

(southwest of Dillon, Co) and the Blue River are part of this

ancestral drainage. The most likely course of this ancestral

river would be a continuation of the Blue River from Williams

Fork Reservoir north-northeastward to just southeast of Willow

Creek Pass. Here it joined other drainage flowing down from

the west slopes of the Front Range. The combination then

turned north-northwestward and continued into Wyoming. This is

the area where the thickest (over 2,000 feet) Paleocene/Eocene

deposits are found. During the Paleocene and Eocene, the

earlier minor uplift that had been present in the Gore/Park

Range eroded down to where it was only slightly more elevated

than these river deposits.

During the initial

Laramide uplifts, the Front Range was lifted to high

elevations and the current Gore/Park Range was only lifted

slightly. (Just enough so that the top sedimentary layers

would erode.) In between the two ranges, the headwaters of the

ancestral Colorado flowed north into Wyoming. Tenmile Creek

(southwest of Dillon, Co) and the Blue River are part of this

ancestral drainage. The most likely course of this ancestral

river would be a continuation of the Blue River from Williams

Fork Reservoir north-northeastward to just southeast of Willow

Creek Pass. Here it joined other drainage flowing down from

the west slopes of the Front Range. The combination then

turned north-northwestward and continued into Wyoming. This is

the area where the thickest (over 2,000 feet) Paleocene/Eocene

deposits are found. During the Paleocene and Eocene, the

earlier minor uplift that had been present in the Gore/Park

Range eroded down to where it was only slightly more elevated

than these river deposits.

During the late Oligocene /early Miocene, there was a general uplift across southern Wyoming and local uplift of the Rabbit Ears Range. The early Tertiary deposits were also capped by local lava flows. The eastern end of the Rabbit Ears Range was lifted several thousand feet. Gravel deposits from the old riverbed can now be found at 11,700 feet on Gravel Mountain (some 7 miles southeast of Willow Creek Pass). The old Paleocene/Eocene deposits are now found at elevations ranging from 8,000 to 11,000 feet.

This uplift forced the

ancestral Colorado to find a new route. It turned

west-southwest to establish its current course over the top of

the beveled Laramide version of the Gore Range. The Blue River

turned west just south of the current Gore Canyon and joined

the Colorado at the west end of the present canyon. Other

steams flowing westward off the southwest side of the new

Rabbit Ears Range established paths that would be used later

by Service, Silver, and Gore Creeks when the recent Gore Range

rose.

This uplift forced the

ancestral Colorado to find a new route. It turned

west-southwest to establish its current course over the top of

the beveled Laramide version of the Gore Range. The Blue River

turned west just south of the current Gore Canyon and joined

the Colorado at the west end of the present canyon. Other

steams flowing westward off the southwest side of the new

Rabbit Ears Range established paths that would be used later

by Service, Silver, and Gore Creeks when the recent Gore Range

rose.

After all this new drainage was established, the current Gore/Park Ranges rose (2nd uplift) during the Miocene. The Colorado River was in place and proceeded to cut Gore Canyon. (The river’s steep gradient through the canyon implies the range continues to slowly rise today.) Initially, the Blue River continued its path across the range (just south of the current Gore Canyon). However, it eventually relocated to an easier route that stayed east of the range where it now joins the Colorado just east of Gore Canyon. (“Let the big guy do the canyon cutting”.) The Blue River’s old route across the Gore Range was abandoned. However this old high, dry valley is still used by highway CR 1 (Trough Rd.) to get across the range.

The Google Earth view below looks WNW across the Gore/Park Range at the old (and abandoned) route that the Blue River used to cut across the range. It looks like a river should be flowing from the foreground to the background through this high valley, but the Blue River abandoned this route millions of years ago.

The high saddle point in the valley is near the dirt road that cuts across the valley in the middle distance. Current drainage is very gentle with water on this side of the dirt road draining towards the foreground while water on the other side eventually drops steeply down to the Colorado River in Gore Canyon. If the current drainages had eroded the valley, then there should be a noticeable ridge at the boundary line between the drainages. The flatness of the valley strongly suggests that a river flowed through - similar to the way that Unaweep Canyon was cut.

Meanwhile, to the northwest of Gore Canyon, the small streams that previously flowed westward from the southwest side of the Rabbit Ears Range were forced to find new routes. As the Gore/Park Ranges rose, these old streams were broken off on the northeast facing slopes of the rising range, as this is where the greatest change in tilt was taking place. The new local drainage of streams such as Service, Silver, and Gore Creeks appropriated the ancestral paths across the crest of the range. For example, Service Creek starts down the east side of the range. However, it has appropriated a section of an ancestral stream that crossed from east to west before the range was uplifted. Service Creek uses this old segment to double back through the crest of the range to flow down the west side.

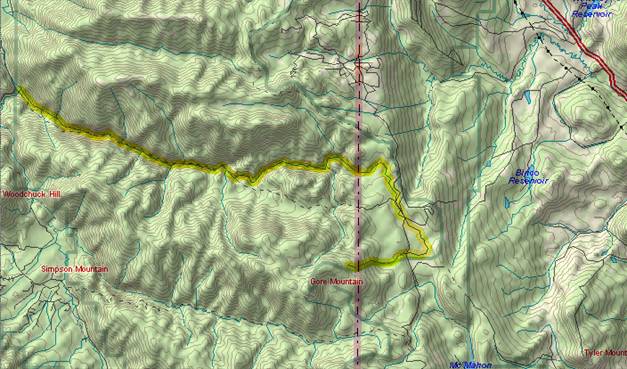

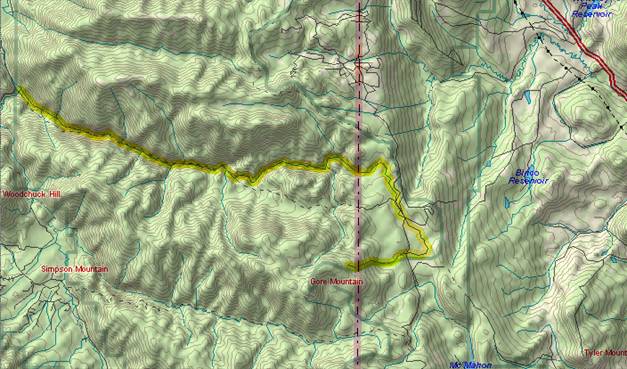

The image above was generated by Delorme’s TopoUSA. Service Creek is outlined in yellow. Note how Service Creek initially flows eastward off the summit of Gore Mountain and then turns westward to cut across the highest elevations of the Park Range.

A new stream, Muddy Creek, developed between the rising Gore Range and the Rabbit Ears Range. It flowed south-southeast for awhile and then it turned southwest to cross the Gore Range at Gore Pass. (A northeast/southwest fault helped by uplifting the southeast side of the valley.) However, similar to the Blue River, Muddy Creek decided it was easier to “Let the big guy do the canyon cutting” and abandoned the high route. Thus, it rerouted further southeast to join the Colorado east of Gore Canyon. Highway builders are always looking for the easiest routes to get across mountain ranges, and Colorado State highway 134 uses the old, abandoned high valley.

The Gore Range rose through most of the Miocene (and probably is still rising), but the Colorado River had established its course. Gore Canyon is the result.

Also please see Origin and Formation of Gore Canyon, Colorado

First, let’s look at some of the unusual/unexpected phenomena that exist in the range.

1) Tenmile Creek cuts a SSW to NNE canyon through the range at about the 9,100 to 9,600 foot level. (Highway I-70 uses this canyon to get through the range.) Peaks exceed 12,000 feet within two miles on both sides of Tenmile Canyon.

2) The Colorado River has cut westward through the range at Gore Canyon. The floor of the canyon is at about 7,200 feet while the rim on both sides exceeds 9,300 feet within a mile of the river.

3) A dry abandoned valley (similar to Unaweep Canyon) cuts across the range a couple of miles south of Gore Canyon. At some time in the past a tributary to the Colorado River flowed east to west across the crest of the range through this abandoned valley.

4) Another high dry valley cuts across the range some 6 miles northwest of Gore Canyon at Gore Pass. At some time in the past, another tributary crossed the range from northeast to southwest through this abandoned valley. (The formation of this valley was probably helped by a NE-SW fault.)

5) Both Gore Creek and Service Creek start down the east side of the range and then double back through the crest to flow down the west side. In both cases, these streams use segments of ancestral rivers that crossed the crest of the range from east to west.

6) The heart of the Gore Range just north of Tenmile Canyon has a jagged, “young-looking” appearance as compared to the rounded Laramide age Front Range just 15 miles further east.

If we look at the area bounded by the Gore/Park Range to the west and the Medicine Bow and Front Ranges to the east, we find a broad area covered by early Tertiary deposits. The east to west Rabbit Ears Range splits this into North and Middle Parks although the Tertiary deposits wrap over the top of the range. Also there are splatterings of mid/late Tertiary volcanics across the top and to south of the Rabbit Ears Range. The Gore/Park Range itself has no Tertiary deposits except for a couple of Tertiary intrusions and some Tertiary lava flows near the west end of the Rabbit Ears Range.

The main feature of the Gore Range is Gore Canyon. Here, the Colorado River cuts a short, deep (over 2,000 feet), young-looking gorge across the crest of the range. If you smoothed out the contours across the gorge, the crest would be about 9,400 feet above sea level. Muddy Creek is a tributary that feeds into the Colorado before it cuts through Gore Canyon. At the north end of Muddy Creek’s drainage (off the top of the view) there are multiple potential exit routes that are less than 9,000 feet including Muddy Pass at slightly over 8,700 feet. To the east of Muddy Pass we have early Tertiary sediments and mid/late Tertiary lava flows overlying Cretaceous layers and still stay well under 9,400 feet. The Tertiary deposits indicate this area has never been over 9,400 feet.

There are two possible ways the Colorado River could have established a path across the Gore Range. Either (1) at some time in the past there was a higher sedimentary or pediment surface east of the range, or (2) the Colorado River established its westward course before there was a (significant) uplift of the range. It has always been assumed that case number (1) was true. However, given that alternate exit routes that stay under 9,400 feet have always been available, the evidence seems to support alternative (2). Thus, we offer the following model.

During the initial

Laramide uplifts, the Front Range was lifted to high

elevations and the current Gore/Park Range was only lifted

slightly. (Just enough so that the top sedimentary layers

would erode.) In between the two ranges, the headwaters of the

ancestral Colorado flowed north into Wyoming. Tenmile Creek

(southwest of Dillon, Co) and the Blue River are part of this

ancestral drainage. The most likely course of this ancestral

river would be a continuation of the Blue River from Williams

Fork Reservoir north-northeastward to just southeast of Willow

Creek Pass. Here it joined other drainage flowing down from

the west slopes of the Front Range. The combination then

turned north-northwestward and continued into Wyoming. This is

the area where the thickest (over 2,000 feet) Paleocene/Eocene

deposits are found. During the Paleocene and Eocene, the

earlier minor uplift that had been present in the Gore/Park

Range eroded down to where it was only slightly more elevated

than these river deposits.

During the initial

Laramide uplifts, the Front Range was lifted to high

elevations and the current Gore/Park Range was only lifted

slightly. (Just enough so that the top sedimentary layers

would erode.) In between the two ranges, the headwaters of the

ancestral Colorado flowed north into Wyoming. Tenmile Creek

(southwest of Dillon, Co) and the Blue River are part of this

ancestral drainage. The most likely course of this ancestral

river would be a continuation of the Blue River from Williams

Fork Reservoir north-northeastward to just southeast of Willow

Creek Pass. Here it joined other drainage flowing down from

the west slopes of the Front Range. The combination then

turned north-northwestward and continued into Wyoming. This is

the area where the thickest (over 2,000 feet) Paleocene/Eocene

deposits are found. During the Paleocene and Eocene, the

earlier minor uplift that had been present in the Gore/Park

Range eroded down to where it was only slightly more elevated

than these river deposits.During the late Oligocene /early Miocene, there was a general uplift across southern Wyoming and local uplift of the Rabbit Ears Range. The early Tertiary deposits were also capped by local lava flows. The eastern end of the Rabbit Ears Range was lifted several thousand feet. Gravel deposits from the old riverbed can now be found at 11,700 feet on Gravel Mountain (some 7 miles southeast of Willow Creek Pass). The old Paleocene/Eocene deposits are now found at elevations ranging from 8,000 to 11,000 feet.

This uplift forced the

ancestral Colorado to find a new route. It turned

west-southwest to establish its current course over the top of

the beveled Laramide version of the Gore Range. The Blue River

turned west just south of the current Gore Canyon and joined

the Colorado at the west end of the present canyon. Other

steams flowing westward off the southwest side of the new

Rabbit Ears Range established paths that would be used later

by Service, Silver, and Gore Creeks when the recent Gore Range

rose.

This uplift forced the

ancestral Colorado to find a new route. It turned

west-southwest to establish its current course over the top of

the beveled Laramide version of the Gore Range. The Blue River

turned west just south of the current Gore Canyon and joined

the Colorado at the west end of the present canyon. Other

steams flowing westward off the southwest side of the new

Rabbit Ears Range established paths that would be used later

by Service, Silver, and Gore Creeks when the recent Gore Range

rose.After all this new drainage was established, the current Gore/Park Ranges rose (2nd uplift) during the Miocene. The Colorado River was in place and proceeded to cut Gore Canyon. (The river’s steep gradient through the canyon implies the range continues to slowly rise today.) Initially, the Blue River continued its path across the range (just south of the current Gore Canyon). However, it eventually relocated to an easier route that stayed east of the range where it now joins the Colorado just east of Gore Canyon. (“Let the big guy do the canyon cutting”.) The Blue River’s old route across the Gore Range was abandoned. However this old high, dry valley is still used by highway CR 1 (Trough Rd.) to get across the range.

The Google Earth view below looks WNW across the Gore/Park Range at the old (and abandoned) route that the Blue River used to cut across the range. It looks like a river should be flowing from the foreground to the background through this high valley, but the Blue River abandoned this route millions of years ago.

The high saddle point in the valley is near the dirt road that cuts across the valley in the middle distance. Current drainage is very gentle with water on this side of the dirt road draining towards the foreground while water on the other side eventually drops steeply down to the Colorado River in Gore Canyon. If the current drainages had eroded the valley, then there should be a noticeable ridge at the boundary line between the drainages. The flatness of the valley strongly suggests that a river flowed through - similar to the way that Unaweep Canyon was cut.

Meanwhile, to the northwest of Gore Canyon, the small streams that previously flowed westward from the southwest side of the Rabbit Ears Range were forced to find new routes. As the Gore/Park Ranges rose, these old streams were broken off on the northeast facing slopes of the rising range, as this is where the greatest change in tilt was taking place. The new local drainage of streams such as Service, Silver, and Gore Creeks appropriated the ancestral paths across the crest of the range. For example, Service Creek starts down the east side of the range. However, it has appropriated a section of an ancestral stream that crossed from east to west before the range was uplifted. Service Creek uses this old segment to double back through the crest of the range to flow down the west side.

The image above was generated by Delorme’s TopoUSA. Service Creek is outlined in yellow. Note how Service Creek initially flows eastward off the summit of Gore Mountain and then turns westward to cut across the highest elevations of the Park Range.

A new stream, Muddy Creek, developed between the rising Gore Range and the Rabbit Ears Range. It flowed south-southeast for awhile and then it turned southwest to cross the Gore Range at Gore Pass. (A northeast/southwest fault helped by uplifting the southeast side of the valley.) However, similar to the Blue River, Muddy Creek decided it was easier to “Let the big guy do the canyon cutting” and abandoned the high route. Thus, it rerouted further southeast to join the Colorado east of Gore Canyon. Highway builders are always looking for the easiest routes to get across mountain ranges, and Colorado State highway 134 uses the old, abandoned high valley.

The Gore Range rose through most of the Miocene (and probably is still rising), but the Colorado River had established its course. Gore Canyon is the result.

Also please see Origin and Formation of Gore Canyon, Colorado

Return to Bridge Timber Mountain

and the Ancestral San Juan River (Part 6)

Continue to the Defiance Plateau, the Chuska Mountains, and Canyon de Chelly (Part 8)

Return to the Main Appendix Page for the Evolution of the Colorado River

Web page generated via Sea Monkey's Composer HTML editor

within a Linux Cinnamon Mint 18 operating system.

(Goodbye Microsoft)

Continue to the Defiance Plateau, the Chuska Mountains, and Canyon de Chelly (Part 8)

Return to the Main Appendix Page for the Evolution of the Colorado River

Web page generated via Sea Monkey's Composer HTML editor

within a Linux Cinnamon Mint 18 operating system.

(Goodbye Microsoft)